Your nausea is mine: The baby i cannot birth

Pregnancy—the female emetophobe’s burden of choice. To be with child or to not subject yourself to a nine-month panic attack. I will never give birth. I am fifteen when I make my choice.

When I am in third grade my science class watches a mini-documentary on Salmonella. In this documentary is a graphic scene where a woman vomits in a plastic bucket during her day job. She has painful diarrhea but this does not phase me. There is a crisp burning under my tongue. In my left breast. In my lower abdomen. This is my source. I am eight.

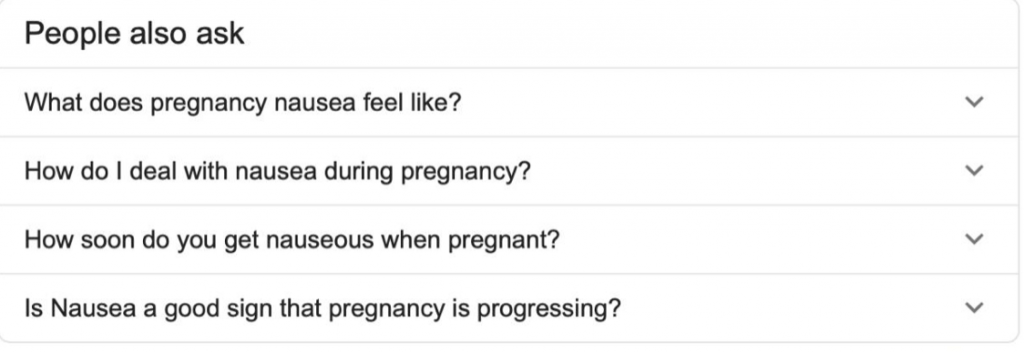

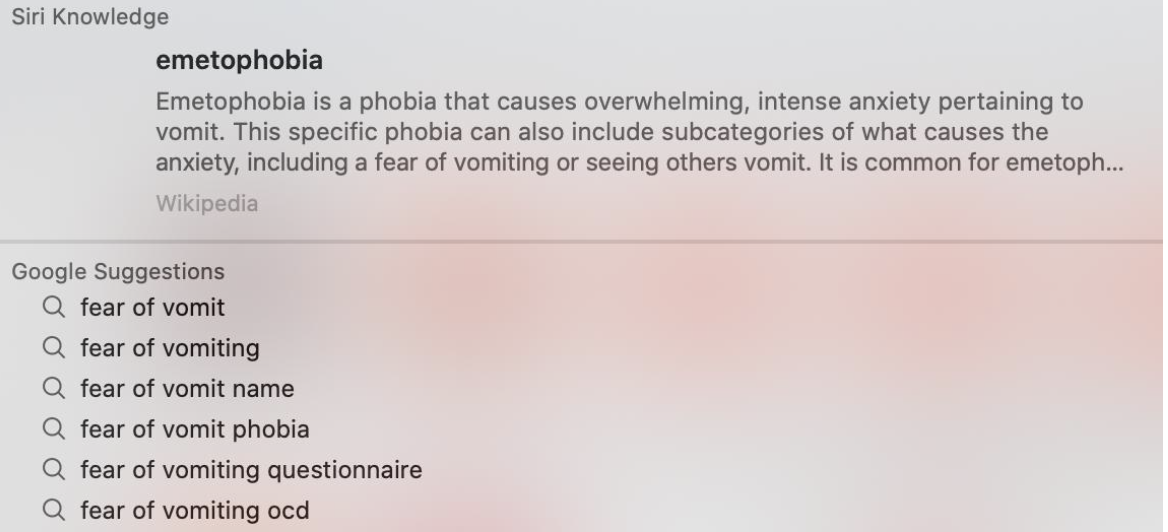

I am eleven when I find the word emetophobia. Siri’s knowledge looks like this.

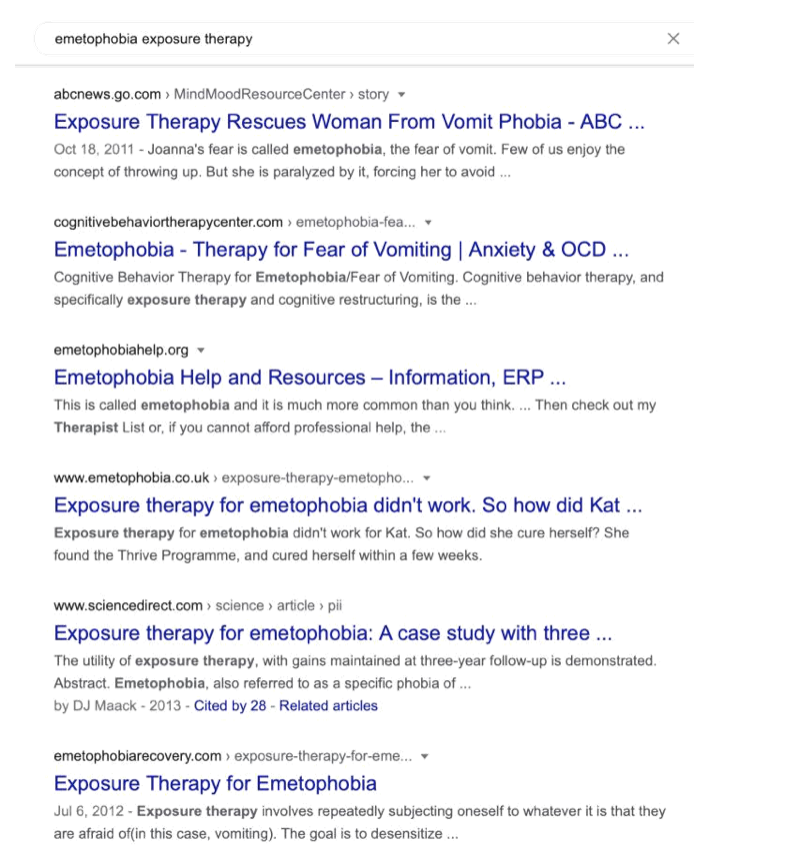

My knowledge spans the Internet as provided by Firefox on a silver Dell computer. The search bar is familiar with my inquiries. I will come to realize in the next eight years that Siri’s recognition is the only recognition for emetophobes.

I am twelve when I have my first panic attack. Advanced math for eighth-graders in my public middle school is Algebra 1. But I do not feel advanced. In retrospect, I know what is going to happen before the boy stands to go to the bathroom one door down. His face pales too quickly.

His raising hand is effete. His voice pleads. My chest pleads. I plead with clenched limbs I do not know I have in a body I do not know I have. A classmate across the room asks his table partner if that girl is crying. I want to tell him yes. She is. But I am she and she forgets how to operate a body she does not know she has. The boy’s vomit is puddled right outside the door. There is no other way out. Every night for a week I wake up from the same nightmare in the same classroom in the same hallway to which I will return in my sleep for years. The same people will provide me with the same sentiments of concern and confusion and a quite frank repugnance. We will reacquaint in increments. Increments with mathematical numbers that I cannot conceive because I failed nearly every test in Algebra 1. The lowest grade I ever receive is in Algebra 1.

I am thirteen when I go to Medicaid therapy at JFK University student training in Concord, California. I tell my appointed therapist I have emetophobia. She tells me she does not know what emetophobia is. Her words are not poignant. We will play Jenga. We will talk about my father. We will play more Jenga. She will recommend breathing exercises. I will not do them. This is what Medicaid can provide me. I do not search for more.

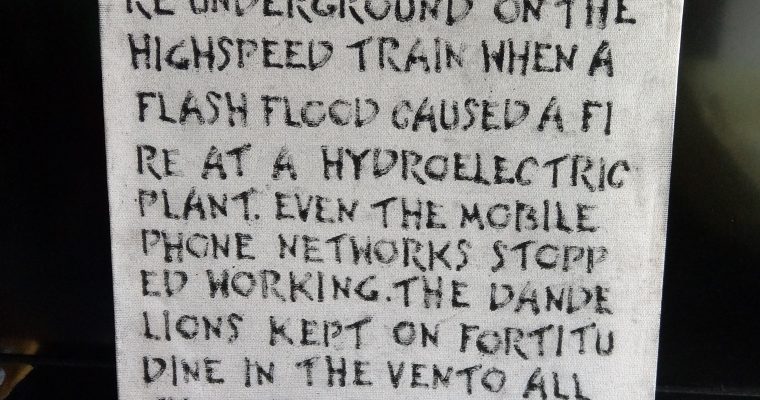

The following is my mantra.

In my own time, I will overcome childhood OCD. I will overcome anxiety. I will overcome depression. I will not overcome emetophobia. I will not mix alcohol. I will not go on road trips with people who get carsick. I will not take birth control. My affirmation is born again with each morning’s early riser nausea.

To be pregnant with a phobia is to wake up with a miscarriage each day.

On a day drinking weekend away in New Jersey, my roommate gets sick in the same air mattress we are lying in together on our friend’s floor. She is crossed. I am drunk and I am out the bedroom door before I see the pooling vomit. The hefty glass doors to the patio open easily when you can no longer breathe in their confines. It is big outside. There are trees. There is a basketball hoop. This is all I remember. I hyperventilate in the arms of my far more sober friend. I reassure her I am fine. She sleeps with me on the couch. I do not look at the air mattress again.

I am eighteen when I start dating my girlfriend. She is the first person I talk to—talk to in words rather than Jenga—about my fear. I one-in-the-morning text her while in Jersey. She is tolerant and forbearing and abstains from judgments. She does not say that she, too, hates vomit. She does not say that everyone hates vomit. She does not say that she, too, hates seeing people vomit. She does not recommend breathing exercises. Still, this is harder than Jenga. I wonder if I miss playing Jenga. The wooden blocks fall harder than vomit falls from mouths.

The second night I sleep with my girlfriend I get nauseous. It is far less easy to feign sound of body and of mind when the girl whose comforter you are under is three inches from your face begging you to talk to her. It is far less easy to feign sound of body and of mind when the girl you love knows that you would rather die than vomit. Her comforter is striped. The window is open. I am wearing socks. This is all I remember. I sit up tight against the wall and am held in ways that are familiar only to those whose stomach cannot be touched. Touch will break me. I don’t want to break my baby. I don’t want an empty womb. I don’t want another miscarriage.

I am my own baby and I do not want to be.

But there is no other way out.

I am nineteen when I make my choice. I will not eat runny eggs. I will not ride a rollercoaster. I will not go on a cruise. I will not take a cross-country bus trip. I will not deepthroat a dick. I will not do chemotherapy. I will not get blackout drunk. I will not be pregnant. I will not have children. I will not give birth.

Author: Alexandra Gold

Alexandra Ebert Gold is a writer born in San Francisco and living in New York City. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Crab Fat Magazine, 12th Street Journal, The Ellipsis, and Jewish Women of Words. She is currently studying Journalism & Design at The New School.