mystic treats

“Hiyiweti lemet’et’ati āleliwo,” you would often tell your daughter; you have to drink life. Sarah is the spit and bone of you: eyes, hands and all. The only difference she inherited from her mother was her ‘keiye’ complexion: red coloured, being descended from the Amhara tribe. But yours was the colour of coffee, freshly roasted, like the way you would sit them on the window sill soaking in the morning sun, overwhelming the apartment with the aroma of home long ago.

“So this is no time for boyfriend,” you would end up saying.

“Aba, you worry too much.”

You had struggled with distracting yourself ever since she went off to university. You missed her questioning face at everything you did, although it was irritating, at times, and yet, like a gentle favour from God, to be looked at with annoyance by someone who has your eyes. She would come back with more things to ask: How was it like when this happened, and that? How did you leave home? What was it like when you came here and went to McDonald’s? Was it like you imagined? Each question, each time makes you twinge in discomfort, but her persistence almost convinces you to see your life as one big, grand story.

You wonder how your parents dealt with ten. There would be the help and the cooks, of course, who would do most things, but the sheer responsibility itself, of leaving your babies so open to the cruel and random hands of fate –

Sarah puts out a hand in front of you. “You are dreaming today,”

You chuckle to yourself, smug. “I am thinking of a story.”

“When you’re done thinking, tell me.” Sarah smiles, not wanting to appear too eager.

You stir then sip your drink. Funny when your kid grows up and can indulge in the same things you kept hidden from them when they were young.

“You put too much ice in mine, Aba.”

“Eh, inidezīya mehoni ālebet, before you forget all your words.”

“I’m not like you, Ba.” She smiles, too keenly.

It is also funny when your kid grows up and is cruel to you in small, finger food bites.

You remember mandarins growing on the front lawn. The sour parts of flesh made its juice taste like sweet liquor. How you would run after school to watch Ama and the cooks teach your sisters how to pick them, and mangos and muzi and you thought girls were the luckiest people in the world. Sara was the one who would save you some and you would rush to her room to eat them in secret, together. You remember her eyes, how everyone mockingly said you were twins because of those eyes, even though it was ridiculous because you were the youngest and she was the first born—

You wore shorts your entire life. They were easier to run around in. The trousers you have on now seem so restrictive, you can barely stretch your legs, and for one moment you think you’re going to be sick until you see Sarah’s hand reach for yours and tell you she didn’t mean it. You squeeze her hand and smile, and put on Adey by Teddy Afro.

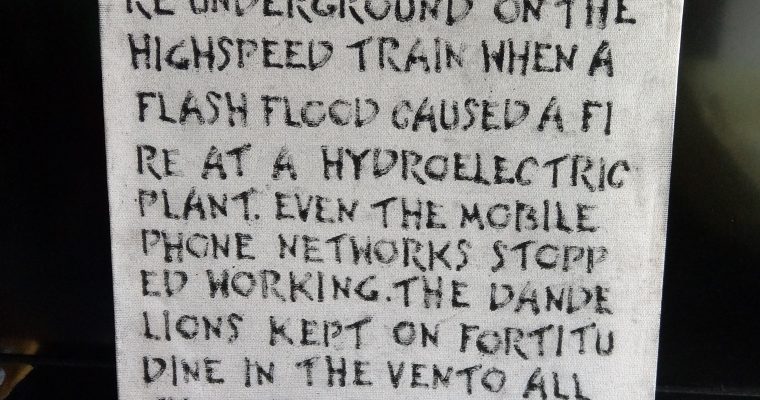

mayidewa tagīsi kayana

ānana shukana

āyi ima

tēlē ēlidawida ītana

ānana shukena

āyi ima

be’āfirīka semayi siri

inatē sitiwelijīnyi gena āyinishini sayi

bemayileka fik’iri wedeshinyi

rasishini set’eshinyi t’utishini

bechigiri tenekureshi

bedihineti t͟s’eḥāyi t’ek’ureshi

āsadegishinyi

sewi āderegishinyi

You came home from school one day and ran straight to Sara’s room.

“Sara, tota, Sara, tota!” you sang as you knocked.

“Abi!” She opened the door tentatively, as if fearing the gust of wind might force you away. “My favorite brother.”

She grabbed your cheeks then kissed them, which you hated then. She pulled you towards her desk, and much to your shock – your tiny childish heart wouldn’t stop beating – there were more fruits than you had seen in your life. It wasn’t just avocados, coconuts or mandarins, but pinks, purples, and blue hued shapes of different sizes and contorts, like jewels, with names which danced an unfamiliar groove on your tongue.

The spiky one caught your eye.

“Pineapple,” Sara said.

“Mein din new? Pine?”

“Apple.”

“No, its not.”

“No, Abi, pineapple.”

“Pineapple…Does it hurt to eat?”

“I went to the market and look – ” Sara yanked a handful of blueberries and popped one in her mouth. “Imported straight from China, and look, Abi!” She stuck her tongue out and there it was: slightly blue, slightly magic.

You were nervous to try them all, fearing you might explode, or change colour, but you kissed your sister’s feet and vowed to never be this happy again. You think of her every time you buy 2 for 1 grapes in Tesco’s.

Sara was starting to change, slowly but irrecusably: she’d wear perfume, wear her hair down and talk like she had the authority of Ama when Ama wasn’t around. That was the last time she allowed you in her room.

“Fifteen-year-old girls shouldn’t be on the phone for this long,” Ama would say.

“She is young, dear,” Aba would sigh. “Let her have her fun.”

They wouldn’t even discuss it if it was one of the others; you’d get two belts and be sent to bed.

You tried knocking on her door one last time. You weren’t sure if you had something wrong, so you came ready to apologize with a bowl of fruit you had just picked from the garden. She opened the door but blocked the entry, and looked at the bowl in disappointment.

“Abi, don’t you have any friends?”

“Yes, but you’re my best,” You said, embarrassed, poking at the fruit. It felt like she was the one that needed to apologize. You offered her a mandarin.

“No, Abi. I don’t have time.”

The phone in her room lit up with sound and she looked at her watch. “Benata, go play outside.”

This was the first time you were ever overwhelmed with green, dead emotion; a bitter, tasteless, green which sat heavy in the pit of your stomach. It gurgled and bubbled and boiled like the evil matter it was, like the insides of a witch’s pot. This was still inside you when Ama sent you to bring food for her and you spat in her drink–

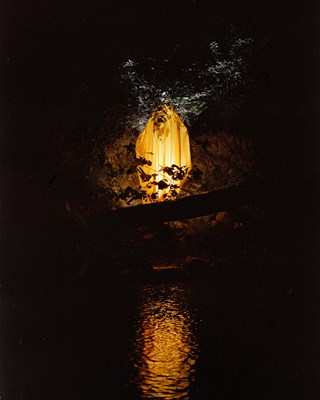

Sara went to Lake Tana with Ama for the weekend and came back with great stories. You were devastated that she didn’t ask you to come with her. She used to tell you before how the whole family went down there when you were still small, and that you floated in water for the first time, above the safety of her arms.

“Ama thought you were too young but I begged and begged,” she would say. “I could tell you would be a good swimmer. Bewanenyineti mikiniyati…I didn’t know when we would come back again.”

It played like a short film in your head that you would watch before you drifted into sleep, but it felt like a cruel trick being part of that memory and not being able to remember any of the scenes. You didn’t really mind though, because it was in Sara’s memory, and she would repeat it whenever you’d ask.

The first thing she did when they came back was turn the TV off while you and the girls were watching. She spoke of swimming under the night sky, how the stars were so close above she reached out and grabbed nine for all of you.

“Behave well, and it’s yours to keep.” She winked.

The girls giggled in excitement. You listened but faced away.

That night, she slept in Ama and Aba’s room, and all the nights that followed until her death. One morning, Ama told the cooks to have the day off and slaved away in the kitchen preparing meals herself. She asked you to take breakfast for Sara; she was in bed and feeling unwell. You don’t know why, or how, but while you were walking up the stairs it was as if the heat on that evil green was slowly burning up, steaming your insides and churning up at you, almost speaking: spit, boy, spit.

You entered her room and her tired face lit up.

“Abi. My favorite brother.”

“Tsh,” You said, with unearned maturity, the sudden and crushing realization dawning upon you that you could never be her favourite when you were the only.

“Abi?” she asked, straining her hands towards you. “Do you have any fruit for me?”

You said your last words to her; you said no. You placed the tray of food on the table furthest from the bed and walked out. When she died, shortly after, you saw she didn’t touch her food, but drank the coffee, full of your poison –

You and the girls found small bags assigned to each of you. Sara had left a star, which was inevitably a rock, in each; while your sisters opened theirs and cried, you held yours towards the sunlight drifting from the window, and saw it, flipping it back and around itself. Smooth-edged, edges gilded with chips and missing bites. A rock, certainly, but peculiarly shaped. Like a diamond.

The neighbors were vulgar when they yelled at you for running around too close to their gates, but they were nice the time they came over, in a way that made you squirm. They told Aba and Ama they were lucky to still hold on to nine; it was very common for children to die without reason. They put their hands on your cheeks and kissed them. You spat at their feet and vowed to never believe in angels again because they kept calling her one –

“Bet’am t’iru neberech,” Aba sighed, and said her name for the last time. “I knew Sara was too sweet for this life. Ever since she was small.”

But you heard something on the veranda, before Ama and Sara went to Lake Tana, that still rings in your ears today—

“She’s only fifteen! Pregnant? Hulum sew mini yilal?”

Then a pause. Everything paused.

“You need to sort it out, āhun.”

You couldn’t tell whether it was Ama or Aba who spoke, their voices often resembling each other’s. But deep down, you know, it was Aba.

You waited in the corner until the neighbours left, and when Ama and Aba went to bed, nestled your small body underneath the mandarin tree. The moon glowed timidly, and you sobbed because she was no longer there, but in everything you saw.

Years later—you were fifteen, maybe—it all came together. Like pieces of a jigsaw; the hushed conversations between your sisters, the gossip of the cooks as they skinned chickens.

“Besm’am!” You heard one of your sisters cry, “She was not the girl I thought she was.”

They deliberately never said anything specific. Your parents, of course, never said anything. Aba would come home from work and go straight to his room, having the cooks bring his food. He would take you all to church on Sundays and that was the only time of the week that you would be in the same room together. He would give Ama a lot of grief, bringing friends over and demanding she prepare the injera fresh, or else, but he never laid a hand on you again. You taught yourself how to drive when he was like this, too consumed by himself to notice that the car was never parked in the garage at night. You searched for jobs and deluded yourself for so long that you wanted to leave because you despised him, but really, and of course, it was Sara’s fate. It hung in the house like a heavy, white mist that everyone pretended was the summer fog that would, like anything, eventually drift.

The final piece of the jigsaw was one you wished you never asked for. “Who was the boy then?” you said.

“Mein? What boy?” Ama’s words stumbled out in haste. She couldn’t look at you after that.

You waited until what would be the end of the school day and took your father’s car. The roads were rickety with stones and dry earth, but it was harder this time because you were shaking in rage and took a few swigs of a bottle that was under the seat. Still, you forced your eyes to follow the road, and forced yourself to remember how to get there. As you turned left there was a man and a donkey carrying his stock, walking on the street without a care in the world. You swore at him as you swerved past.

“The road isn’t made for you, debdeb!”

The man remained indifferent but the donkey looked puzzled to have met your middle finger on his casual stroll, as if to say, “We all have places we’re rushing to,” or “If anything, I should be the one swearing.”

You pulled up on the street opposite the school. Swarms of girls who looked so much like her flooded the gates; with the red blazers and checkered skirts, you could tell a Nazareth girl from a mile away. Two suited guards stood at the gate, both broad and charged with pre-eminence. They wore sunglasses, so you searched the rest of their faces for any slight slips, any twitch, a wriggling of the nose, a licking of lips, anything that could give one of them away. Maybe the man responsible for all of this left when he heard the news. Or maybe he was standing right in front of you. Pondering this, you sank in the worn-out leather, fiddling and smoking one damp cigarette after another. You questioned whether you should have brought your father’s t’emenija he keeps in a drawer in his office. You wouldn’t even know how to use it. There was a possibility you would have used it on yourself. As much as you wanted to claim some sort of revenge, something you could point at and say, at least, justice was served, you realized that justice would be Sara in the seat next to him telling him to go back and apologize to the donkey, which means, ultimately, justice is merely a wish, as hopeless as calling the dead to rise.

“What about the man?” You would ask.

“He deserved it.” She would shrug, and then, wink at you.

You often imagine her, making comments at the things you’d see or responding to what you’d say, but then she’d leave every time you’d try to apologize.

“It’s too late for that, Abi.” She would say, fading.

Hours passed. When the street was empty of girls and guards, you bowed your head against the wheel, and screamed, and screamed, and screamed.

You took the car and never came back home again.

You remember the time Sarah would come with you to jobseekers, when she was still young, pointing at different posters advertising local work.

“TEACHER WANTED.”

“MECHANIC FULL TIME.”

She would point and say you could be this or that, repeating words you often said to her, that you could be whatever you wanted to be. You would look at the posters and smile, and say maybe, maybe.

“Or a chef? You’d be a great chef.”

You tried to explain that cooking is something you only like to do for people you love.

“But everything is better shared, no?”

“That’s right, but some things are better secret,” You watched her face fall into a frown, and before she could respond with another case, “And I hate people telling me what to cook, how to cook it, debdeb! I like things my way.”

She smiled, and then rubbed her tummy. “What’s for dinner?”

She enjoyed watching you, and you enjoyed her company, when you would prepare stews, tibs and kitfo, with injera. She used to take some in her lunchbox to school, despite the strength of its aroma, and you could not have been prouder.

“Gobez yene lidge…she came out from my side,” You would say to your wife mockingly.

“Tasik’aleh. She came out from me,” She would poke at you.

“You know, liji iyalehu, it was bad luck for men to be in the kitchen,” Your words barely audible, disrupting the flow of music that has been playing for a while now.

Sarah frowns, then nods. “Would have been worse luck if me and imayē had to cook.”

Sami Dan is playing now, Kalesh Anchi. It’s too sad and slow and you rush to skip it.

When you held your child for the first time, your childish heart wouldn’t stop beating, and you realized you broke all your childish vows. You decided to name her Sarah so her name could echo and bounce off walls, but you almost regret it at times like this, when her eyes get bigger with each sip.

* * *

Under the sky of the sky

Mother is pregnant just when she is pregnant

You fell in love with inseparable love

You gave me your breast

You’re in trouble

Reduced the poverty of the sun

I grew up

You made me a man

- Translation of Teddy Afro’s first verse of Adey

Author: Meron Berhanu

Meron Berhanu is entering her third year of studies for English and Creative Writing at Royal Holloway. SHe has also been shortlisted for the Beyond Borders 2019 Short Story Competition. Despite coming from a non-creative household and despite worries that a working-class black girl from Kilburn can make it into the very white and middle class dominated playing field of literature, the support from HER family and community has been monumental.