canaan

Abe didn’t think it needed a funeral, but he complied with his wife and pulled over. The

opossum’s flattened tail blended into the asphalt shoulder where someone had dragged it aside, its innards expelled, its hind legs mangled. Flies flitted in and out of its unhinged mouth, and when he opened the driver door, the smell made his eyes water. He kept an old blanket under the back seats, a reminder of the sex he and Sarah had years ago on their star-gazing dates. He used to dig it out in hopes to make her laugh, and in a more buried hope to relive one of those younger moments. Now, he used it to scoop the dead opossum off the highway.

After moving the groceries up to the backseat, he set the carcass in the trunk, hoping it

wouldn’t slide on the sharp turn into their cul-de-sac and he’d have to shampoo the walls.

“Don’t get any of it on the squash,” she called from the passenger seat.

“It’s all in the backseat.”

She was breaking open the barbecue chips when he climbed back in. Tandem grocery

shopping had been her idea. She didn’t trust him to go alone, list or not. The current excitement in their lives was seeing whose mind would decay quicker, and while he sometimes forgot to buy hummus, her requests, such as having a funeral for roadkill, reeked of senile rot. He joked—to himself and only half-heartedly—about throwing her into that nursing home whose fliers kept winding up in their mailbox. She drew the chip bag closer to her chest when he reached for it.

“You got it on your hands,” she told him.

Back at the house, she watched as he dug a hole in the backyard. After all those years of

mowing and maintaining, he was surprised at how little he cared when he first drove the shovel blade into the grass. Their little piece of the world they had bought, always manicured and empty. He had mowed that morning and the clippings clung to his legs. It wasn’t long before he felt winded. It was all for her amusement, of course. She was showing him how weak he became. He could hear that soft, haunting voice.

Where’d my big strong man go? He had been strong, back when he dug a hole in their old backyard years ago. He hardly paused, hadn’t stayed to look at the upturned mound.

The blanket was beyond salvaging. He kept it in the shoebox along with the opossum, too

tired to consider the loss. After he filled the hole, they stood under the ash tree without a word. Despite the familiarity, he grew restless in her silence. In that heavy lack, a core of something cold and hardened.

“I’m not doing this again,” he spoke into it, then regretted it.

She hardly looked at him. “What do you mean?”

Communication is key. The maxim of marriage. It’s the key to a fight, that’s what. They

fought whenever he communicated.

“This,” he answered. “It’s obvious what you’re trying to do here.”

Maybe he wasn’t so tired after all.

“What am I doing?”

“If this is your way of blaming me—” No. He was too tired. He left it unfinished and

went inside without the shovel. A dull throb in his shoulder followed him, as if she wordlessly put it there.

They mapped their home by compromises, voiced and unvoiced treaties, items kept and

placed in strategic utility. He could navigate the rooms by the times he settled for a decorative vase or wicker chair. The familiarity made changes stand out, which was why he stopped in the living room with only a towel, dripping water onto the rug. Sarah’s mother’s urn sat on the mantelpiece, another silent act of defiance, an encroachment on a treaty.

Her mother’s death had been easier. The old hag never approved of him, and she and

Sarah grew distant. At the old house, they first kept the urn in the bedroom. He constantly felt the dead woman’s haunting disapproval while he slept, and he proposed to move her to the storage room. Sarah had allowed it. She never argued much then. She had always been tired after sneaking off every night to the burial. He sometimes sat on the unpacked bassinet in the storage room and watched her white ghost float in the black of the yard. When his work had offered a transfer to their East Coast location, he took it. The new homebuyers had asked about the little grave toward the woods. A dog, he told them.

Abe took the urn and put it back in the guest room.

Sarah refused to talk after their little opossum funeral. He was fine with the couch again.

They didn’t use each other for much beyond counterweight on the mattress. The knowledge that marriage and bachelorhood carried the same loneliness had settled like a spring of cold water in the deepest parts of him. A partner, reduced to something rather had than not, a one-night stand carrying on for thousands of nights.

As he slept, he dreamed of a small boy standing in their yard, wrapped in a blanket,

covered in dirt. He was laughing, showing off long sharp teeth, still laughing as his eyes receded until they were black and beady, still laughing as the whiskers sprouted above his lip. When he woke, there was a distant scraping, something churning far away. He opened an eye. The blue dark. The hallway light was on. He sat up.

“Sarah?”

Through the glass patio door, the sensor lights cast the backyard in a sterile white. She

stood under the ash tree, her thin nightgown veiling the empty space her gaunt body couldn’t fill.

“What’re you—” He pulled open the patio door and a flash of gray bolted past his feet,

chittering, scraping the hardwood, stumbling against chair legs, knocking down a picture frame, and disappearing into the bedroom. Abe stayed frozen, a hand on the door.

“I heard the scratching.” She came to him wide-eyed and dragging the shovel behind her.

Over her shoulder, a mound of upturned dirt. The blood-and-feces-stained blanket laid unfurled across the grass. She grabbed him by the arm, and he couldn’t help but notice how foreign that touch felt. “I heard him.”

He looked at her. Her face was lined like a road map of unfamiliar freeways paved over a

land he used to know. The frayed and graying hair, the tapered breasts, the dirt and grass

clippings clinging to the hem of her gown. If this was what she became, he wondered what she saw with those wide eyes on him.

Chattering sounded from their bedroom. He took the shovel from her and crept back into

the hallway. Surely, it wasn’t him she had fallen in love with. One can never truly know a person. It wasn’t him she had loved but an imitation of him. A one-man show in the theater of her mind, his role played by a more kind, more loving, and more handsome actor.

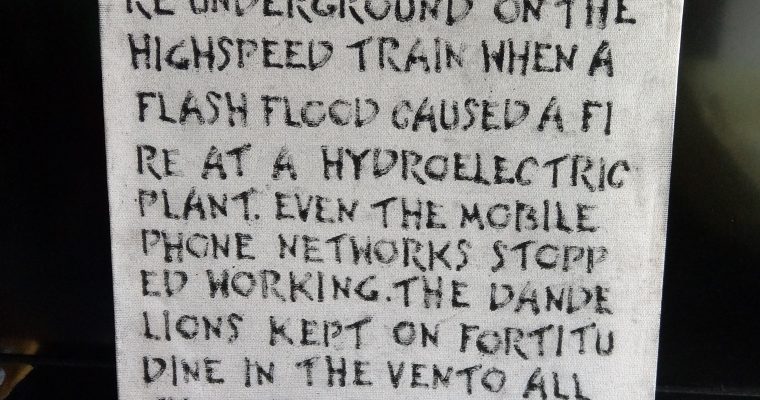

The scraping and chattering reverberated down the hallway as if coming from inside the

walls, vibrating into his feet. He tightened his grip on the shovel as he stepped onto the bedroom carpet, the open door against his shoulder, the room black and blue and still. The scraping and chattering stopped. A cold silence.

In a corner, a shadow shifted. He swung the shovel. Broken glass, like falling water,

cascaded down in shimmering glints. The opossum darted back into the hallway and Abe stormed after it, watching it slip through the ajar guest room door. Sarah was standing in the kitchen, white in the dark of the house, wringing her hands.

He had seen how it changed her. He had offered other options. Adoption, egg donors,

surrogates. Before it was too late to keep to the linear way of things. She said no to all of them. Maybe she was scared. Or perhaps she had wanted to see someone, a person who looked like them both, have a go at being happy.

He could feel electricity through his muscles. He kicked away the guest room door. The

opossum sat perched on the nightstand, seemingly uninjured, the fur on its back arched in a serrated crest. It hissed. He swung and it leaped onto the bed. The shovel shattered the urn. He breathed in the ash as he swung again, through the air and into the mattress.

He chased the opossum out the door as it skittered across the hardwood, down the hall,

and out the open patio door. He watched it disappear out of range of the sensor lights.

Somewhere in the dark, a neighbor’s dog bayed.

He let the shovel clatter to the floor and slumped to his knees, coughing. Sarah’s mother clogged his sinuses and scraped at his lungs. Pain echoed in his shoulder. His whole body felt weak, spent, stretched thin over raw aching muscle. Somewhere behind him, a fly buzzed in the quiet.

Gentle hands, like the falling of a thin blanket, moved along his arm. He could smell her,

fresh dirt and the more familiar scent of their bed. Had it been her smell he had longed for,

whenever he got home from work, or the smell of the bed? Her face was wet, pressed into his neck. He put his good arm around her and they both sat on the hardwood floor in the dark, waiting for light to come. Once it did, there would be a big mess to clean up. He knew Sarah didn’t trust him to do it by himself.