ORNITHOLOGY FOR DAUGHTERS

I used to be scared of crows because my father would see a group of them and whisper to me underneath his breath, “Diablo.” We’d be roller skating down the streets of our neighborhood in Phoenix, Arizona — my dad in tight, neon shorts and I, in a pair of pink overalls, while the temperature outside rose to 117 degrees. “Stop mija,” he said sternly, bending his knee like an Aztec warrior and moving the non-dominant foot back to slow down. His eyes locked on something in the distance, but higher up than eyesight. “Don’t look at them! Look away!” He grabbed my shoulders and spun me around. Over my shoulder, I caught a glance of a crow sitting on a powerline. To me, it looked like peaceful messenger. To me, a crow was a thing of beauty.

How could anything in nature be evil?

Then my father would remind me of the snake in the bible. How it was the snake that convinced Adam to eat the apple. When he was done warning me of the snake in the garden, he’d whisper, “Diablo,” underneath his breath.

My mother died on the day she said she would die. None of us were surprised by the fact that she predicted her death considering she wrote a book for my cousin. Oh, you’ve never heard of a death book? Come closer, you’re gonna want to hear this.

It was the entire account of what would take place in my cousin’s life. It included every significant life event my younger cousin would experience in her lifetime: a broken kneecap from a carnival ride in Ojai, California, the crocodile that almost married her at the river between Honduras and Costa Rica, and even how she would eventually fail miserably while launching a rocket to Mars. “

There should be more women in aerospace. It’s not that hard. It’s like anything really. Once you learn it you know it. Just like baking a cake,” she would say to my cousin during the holidays. “But if you want to build rockets you’ll have to live in one of those God awful places like Arizona or New Mexico. Best to stick to satellites. Stay in California.”

My father didn’t believe my mother was a medium, not one bit. Finally, one day when we were all sitting around the coffee table, my mother had enough. “That’s it. Don’t believe me? I’m calling your mother,” she said, and right then and there, she spoke to my grandmother. My father knocked his head back and laughed. “Mediums are diablo,” he said, loud enough for my mom to hear.

My mother turned to my father and took a sip out of her coffee mug before saying in her voice, sweet as a nightingale, “She says you better start washing between your toes, Rigoberto.”

“She said that? What else did she say?”

That was the second time I ever saw my father weep.

In our neighborhood, my mother was sort of a big deal. Okay, she was a very big deal. Everyone asked her for advice. She could take one look at you while you were washing your car or standing in the soup line at the co-op and tell you exactly which organ would fail next. If you were pregnant, she would call you tell you when your little one would slip out. She predicted our neighbor’s birth. Right outside Gary’s Surf Shop at 11:12pm under the Snow Moon.

I think my father was jealous of her mystique and grace. He’d come home from Mcdonald’s, a pocket of hard-earned money to feed us and my mother would be outside tying seashells together to make a

hammock for a wounded puffin named Pellegrino.

When she told me how she would die, she surprised me with a flight to New York City for the weekend.

“We’re going to get facials from a rhinoceros,” she said.

After our facials in mid-town we walked 19 blocks to Gramercy Park . My mother reached her hand into her fur coat and pulled out a small copper key with the number 383 on it.

“There are only 383 keys in the entire city that give you access to this very park,” she said.

Her nose was red from the cold.

I shook my head and lit a cigarette. My mother hated me smoking but I knew why we were here and I wanted her to see my misery.

We sat on a bench on the north side of the park and my mother hummed to herself. We did this a lot back home — we’d go for a walk, find a nice bench, and sit there for hours in silence taking in the sounds and smells until it got too cold or dark that we had to walk home. My mother called it meditation. My father called it running away from responsibility; a waste of time.

We sat, my mother’s nose getting redder by the minute, and I saw a tiny, handwritten sign pinned to a wooden post in a flower bed.

“No dogs, no alcohol, no smoking, no bicycling, no hardball, no lawn furniture, no Frisbees, and definitely no feeding of any of the birds and squirrels that possess the discerning taste to have taken up residence in this rarefied haven. Birdseed and peanuts draw rats, and much like trespassers and litterers and groups of more than six persons, rats are not tolerated.”

A bird that I was not able to identify at the time flew down and landed on my mother’s lap. She reached into her pocket and pulled out a handful of dried corn and fed the bird the corn and the #383 key and that night, over a spaghetti dinner on the upper east side, she told me how she would come back to me as a bird in the afterlife.

“It would have been more dramatic if you would’ve just left me a video or something,” I said, twirling the pasta over my fork.

“You know how I feel about live taping honey,” my mother said, shaking her head in annoyance.

“I know but like what do I do now? I mean now that I know that you are for sure dying and that you are reincarnating as a bird? Plus, what’s dad going to say?”

“You go on living as you would. Cherish our time together. Learn how to do laundry. Learn how to listen to them.” She said “them” in a hushed voice as if we were standing in the middle of the bird aviary in the San Diego Zoo and she was worried one would poop on our heads.

She refused to tell my father. She knew he wouldn’t be able to stomach it.

That summer I read every book I could on birds.

How to Read Bird Tracks in the Snow, Year of the Bird, Bird is the Word, Ducks and Stuff, The Private Lives of Unloved Birds, The Seabird’s Cry: The Lives and Loves of Puffins, Gannets and Other Ocean Voyagers, The Dove: A Biography, The Wonder of Birds, Birds Are Life, A Life With Birds, A Bird Lover’s Handbook Birding Without Borders and many others.

It was during this time that I started working on my own manuscript: The True Account of My Life as the Daughter of a Medium Who Communicates Through Birds And Who Has A Mexican Father Who Hates Birds, But Crows Most Of All Because He’s Convinced They Are Demons Incarnate.

I’m still working on the title.By the time of my mother’s death I was a licensed ornithologist. Of course, it was not a real license (what a waste of money!). You can get licensed online and print out your certificate and take it to a nice store like Michael’s and write your name on a ticket stub and have them call you in 4 weeks when the frame is ready for pick-up and you can hang that frame in your apartment and use it as proof so that when anyone questions your credentials you can point to it and say that yes, you’re an ornithologist.

When the bus finally hit her at the corner of Cape May and Bacon at 5:55pm on a Sunday afternoon, I can’t say it didn’t make me think of popcorn. The way it stays in the microwave too long and you wait for the long pause between pops until the very last one pops and you know, without any doubt, that the bag is done. Everything is popped. No kernel left behind.

I wait three days. The three longest days of my life to meet my mother as a bird. I guess she had other stuff to sort out before she could start the reincarnation process.

“Sorry I’m late,” she squawks.

She finds me on a park bench, where we did the majority of our meditating. I’m smoking a cigarette and finishing a bottle of Merlot in a paper bag. My father is sitting beside me with a scarf around his face. “Cigarettes are diablo,” he says, underneath his breath. I used my state of grief to mask my addiction. He knows I’m on another plane. Where smoking and lung health are bottom of the list and crying by the ocean while chain smoking Marlboro Lights is first.

My mother appears in front of us in a violet shade of a Sage-Grouse. I can see into her eyes. She is there. Somewhere underneath the feathers and beak.

She swoops up right next to me and stretches out her long neck to snatch the cigarette out of my hand. Like a human standing up, she jumps off the bench and heads straight to the ocean to drop my cigarette in the water. She’s making a statement. She’s still my mother. She still cares about me.

My father sits on the bench, dumbfounded. Mouth wide open.

“Diablo,” he says, underneath his breath.

“That’s littering you know!” I yell at her through sobs, but the sound of her wings and the crash of the waves drowns out my cries.

The next morning I find her hopping along in the front yard, picking at the grass. She’s a snowy egret.

“Hi mom.”

“Hi honey.”

I realize she was right. She was in fact, communicating with me as a bird. She was a medium bird. Not a medium-sized bird. She usually opts for larger birds, although she switches it up from time to time.

My father walks outside with a sling-shot. “In Mexico, we used to kill them like this,” he says, a smile spreading across his whole face like a joker. He bends down to find a rock tiny enough to fit in the leather sling.

“No, not that bird! Not any bird!” I scream and leap off the steps to protect the egret. “They’re rodents with wings. I don’t want them here!”

In a panic I do the only thing I could think of. I run up the stairs and into my bedroom to tear my certification off the wall. Wouldn’t you?

I find my father outside, feet shoulder-width distance apart, one eye squeezed shut to narrow in on his target: My mother.

“Dad, if you try to hurt ANY bird I will have to arrest you,” I shove the certificate into his chest.

“Mija, what is this?”

“Oh this? This is important. It says that I’m an ornithologist certified by the state of California and I have a right to arrest you if you hurt a bird or say anything harmful about a bird for the rest of your life.”

It doesn’t say that but I trust my dad would never read the fine print.

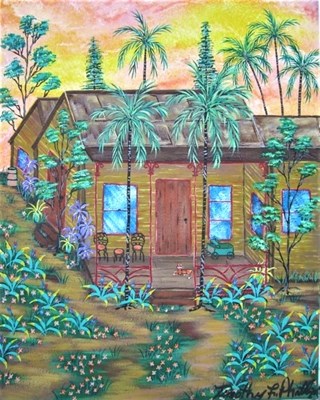

The next morning, I walk to the ocean and sit on a bench made of old surfboards. This was our spot. The tide is high and the mist climbs up the cliff and mixes in with the fog. It makes me feel like my feet are hovering above ground. Like I made it to heaven too.

A flock of a hundred or more Red-necked Phalaropes pick up speed above the crashing waves in a dance that looks like something between a painting and a ballet. Their wings skim the water like graceful ballerinas.

I know it means, “I love you.”

Now, I suppose in the afterlife, words don’t come easy.

My father walks over to the bench and sits down. He follows my line of sight out to the water.

“They’re beautiful,” he says, underneath his breath.

Author: Lauren Villa

a writer based in San Diego, California. She is a graduate of the Johns Hopkins Writing Seminars program. She likes to write about coffee shops, sex, space, and death. Her work has appeared in Sky Island Journal, Thoughtful Dog, and coffin Bell. She is working on her first novel.

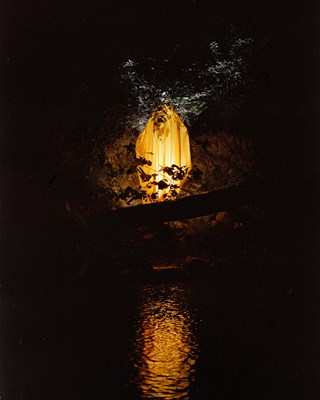

Photographer: Vicky Martin

Vicky Martin enjoys bird watching and taking photos during outdoor adventures.